Chinese inmates who fought during the Second World War will be released from prison as the country prepares to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of the war.

Through the amnesty, China seeks to grant solace to those who sacrificed their lives for the service of the nation during the conflict. However, analysts have seen the move as mere political rhetoric with no legislative goal in mind.

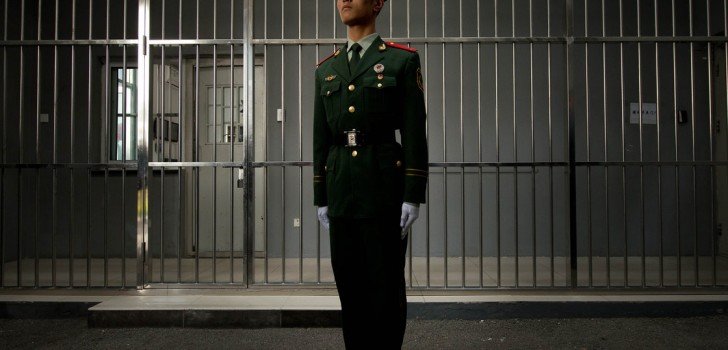

China’s legislature announced that four categories of prisoners who were sentenced before January 1 would be released. These include those who fought against both the Japanese and the Kuomintang, those who fought in wars after 1949 to “protect the country’s sovereignty, security and territorial integrity”, those who are older than 75 and are physically disabled and those who were under 18 when they committed their crimes.

However, a statement from Li Shishi, head of the National People’s Congress Standing Committees legislative affairs, said that the amnesty would not be granted for inmates who were accused of serious crimes that include murder, bribery, rape, corruption, terror offences and organized crime.

According to Shishi, the exceptions to the amnesty were because of the ongoing crackdown by the nation on corruption, and also to maintain public security and safety.

This is China’s seventh amnesty since 1949. The last one occurred in 1975.

The Standing Committee will make their final decision regarding the proposal by Saturday. Afterwards, it will be up to the country’s high profile courts and intermediate people’s courts to determine who will qualify for the amnesty.

Analysts, however, have termed the move as mere “rhetoric” that is based solely on politics and not legal issues. Patrick Poon, Amnesty International Chinese researcher said, “We can’t see any rationale for maintaining the Chinese government’s call for promoting the rule of law.[The amnesty] is more political than legal.”

The move toward leniency has led many to ask whether high profile inmates such as Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, would be released.

Zhang Lifan, a Beijing based political analyst said, “That’s very unlikely, or impossible. There’s leniency on the surface, but only a small number of prisoners will benefit.”

As China marks 70 years since the end of World War II on September 3, the amnesty shown to prisoners will set it apart as a country increasingly becoming humane. It will move closer toward shedding its image as an elitist government with tough laws for small fish and more toward an equal society before the law guided by law and moral obligation. Or at least that’s the plan, which can often differ from the hard realities of the sprawling country.

Stay Connected