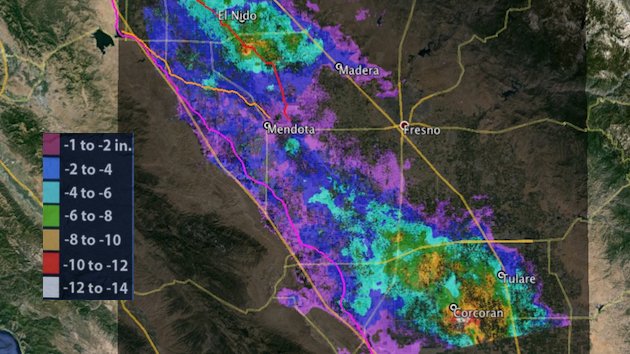

NASA’s latest satellite images reveal that California is sinking even quicker than scientists had previously thought.

The new images reveal some regions of the Golden State are sinking over 2 inches per month, placing a serious burden on the state’s infrastructure.

Though the sinking has long been a major challenge in California, the pace is accelerating because of the extreme drought in the state that is triggering voracious groundwater pumping.

In a formal statement, Mark Corwin, the director of California’s Department of Water Resources, said, “Because of increased pumping, groundwater levels are reaching record lows — up to 100 feet (30 meters) lower than previous records.” He added, “As extensive groundwater pumping continues, the land is sinking more rapidly, and this puts nearby infrastructure at greater risk of costly damage.”

The increased groundwater pumping could have lasting repercussions. If the ground reduces in size considerably, and for a long time, it can permanently lose its capacity to hold groundwater, the study revealed.

The sinking of California is not a new phenomenon: California has experienced the phenomenon for a long time, and some areas are now a number of feet lower than they were in 1925, according to a U.S. Geological Survey.

Certain chronically affected areas are reducing at an amazing rate. The area around the Tulare Basin, including Fresno, sank 13 inches in only eight months. The Sacramento Valley sinks about 0.5 inches every month. The California Aqueduct, a complicated network of canals, pipe and tunnels that channels water from high in the mountains of Sierra Nevada in central and northern California to the Southern part, has sunk 12.5 inches and most of that was in the past four months.

The intense thirst for groundwater in some areas is mainly a consequence of agriculture: Most of the state’s farming production rests on the fast-sinking areas around some of the state’s most dying out river complexes, notably the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers.

As the temperature and lack of rain have depleted surface-water resources, farmers have opted to turn to groundwater to maintain their crops.

The subsidence isn’t just an aesthetic challenge; highways and bridges can sink and crack in hazardous ways, and structures designed for flood control can be compromised. In the valley of San Joaquin, the sinking ground has damaged the superficial shell around thousands of privately controlled wells.

“Groundwater acts as a savings account to provide supplies during drought, but the NASA report shows the consequences of excessive withdrawals as we head into the fifth year of historic drought,” said Corwin, adding, “We will work together with counties, local water districts, and affected communities to identify ways to slow the rate of subsidence and protect vital infrastructure such as canals, pumping stations, bridges and wells.”

Stay Connected